White Australia, Migrant Bodies: The Colonial Echo That Never Ends

By Walter Simón

01/09/2025

I am a Kaqchikel Maya living in Australia.

Since I arrived in the city of Brisbane, I have experienced what I already suspected: structural racism, symbolic violence, and constant surveillance of bodies like mine, racialized and migrant. It did not take long to notice that, beyond the postcard image of a developed country, Australia is a nation profoundly marked by colonial legacy, white supremacy, and a systematic exclusion disguised as “order”, “civilization”, and “progress”.

A week after my arrival I started classes and, as often happens, my first connections were with other Latin Americans. They spoke of how good life is here: safety, stability, opportunities. But amid that admiration, the first symptoms of the problem emerged: “Watch your bike, the Aborigines steal”, “They get violent when they’re on drugs”, “Better not get close”.

I was surprised—though not too much—that it was also migrant people, themselves racialized, who repeated these discourses. But the Latin American mestizo carries within a contradiction that, as María Galindo says, must be politicized. The mestizo embraces their European heritage while denying, devaluing, or silencing their Indigenous roots. And so, whiteness continues to function as aspiration, as standard, as system.

In Australia, the term used for the First Peoples is “Aborigines”, not “Indigenous” or “Indians” as we were called in the Americas. It seems like a minor detail, but it contains a symbolic difference I will address another time. Today I want to focus on how whiteness continues to produce hierarchies that dehumanize others.

Kaqchikel Maya author Aunara Cumez affirms that racism is not a remnant of the past, but a colonial device that organizes the present. “Colonialism was, is, and will be unless we challenge it”, she says. And this is clear both in the Americas and in Australia: the invaders never left; they simply changed costumes and proclaimed themselves citizens, patriots, leaders. The wealth remains under their control. The State answers to them. Policies favor them. And everything that does not fit their mold is suspicious, disposable, or criminal.

What has happened in Australia is not an isolated case. Around the world we are witnessing a troubling resurgence of authoritarian, nationalist, and deeply racist right-wing movements. Figures like Donald Trump, Javier Milei, Nayib Bukele, Daniel Noboa, and even Benjamin Netanyahu in the Middle East represent the same pattern: leaders who preach hatred, redefine migrants as threats, and praise brute force as a model of power.

Trump and his MAGA (“Make America Great Again”) movement established a discourse that has been replicated in different contexts: closing borders, criminalizing those who flee violence or poverty, reinstating the figure of the “other” as danger. And now we see how that discourse reaches Australia, when marches like “Australia First” are called, prohibiting foreign flags and blaming migrants for the housing crisis.

Isn’t it the same pattern? Nationalism, xenophobia, racism, denial of rights. All of it fueled by algorithms that amplify hatred, and by platforms—like X/Twitter—that become echo chambers for modern fascism.

The 31st of August March: Shameless Supremacy

On 31st August, 2025, an openly anti-migrant march took place in Australia. Under the slogan “Australia First”, it called to “save the country” from foreign invasion. The irony? This country has belonged, for millennia, to the Aboriginal peoples. Not to the descendants of settlers. Not to the heirs of European convicts.

Aboriginal scholar Aileen Moreton-Robinson explained it masterfully in her work The White Possessive: white nationalism is based on an illegitimate relationship of possession of the land, which can only be sustained by systematically excluding the true owners of the land (the First Peoples) and those who do not fit the white, productive image of the “model” citizen.

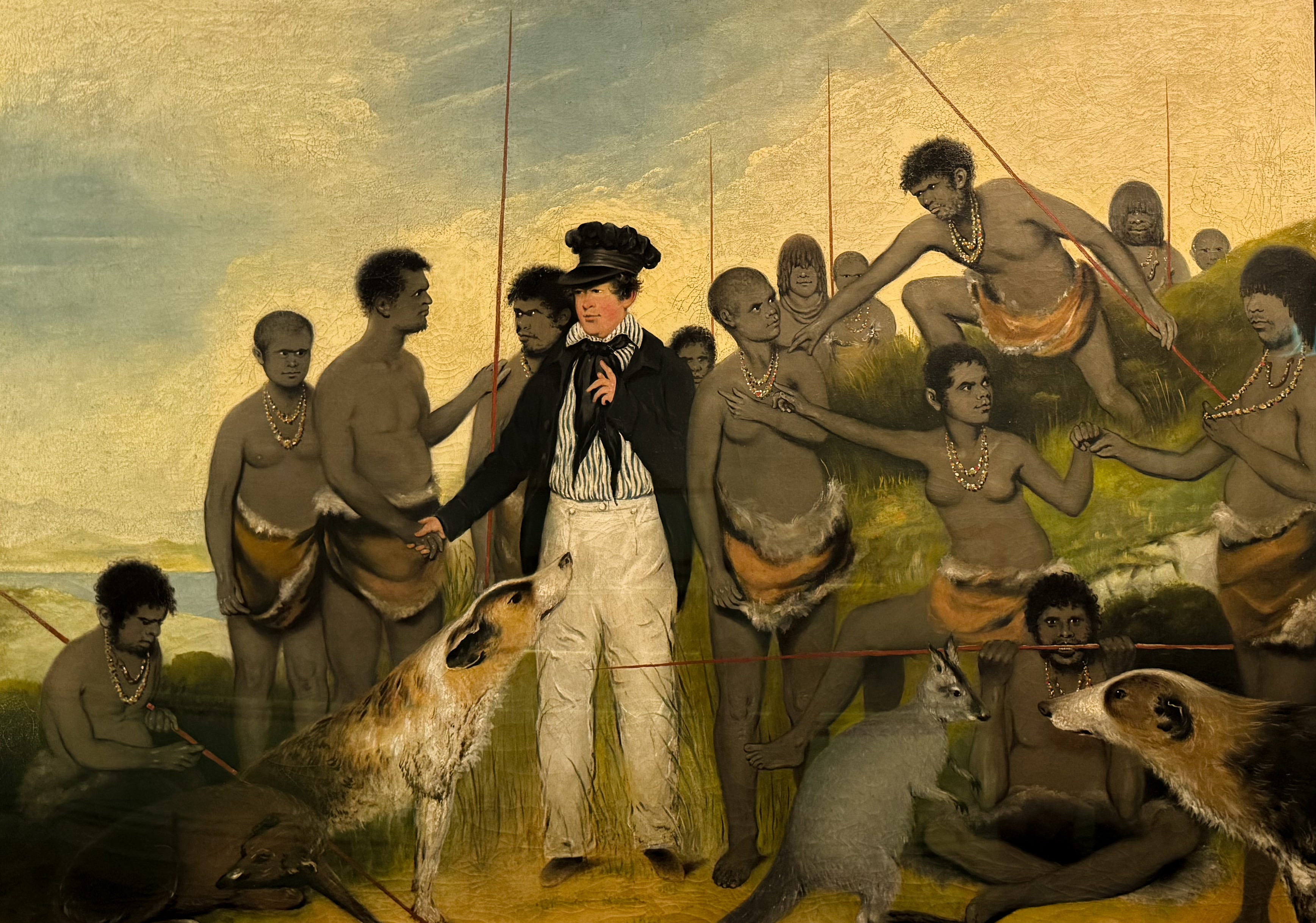

Photo: painting from the “Dispossessions and possessions” gallery, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, photo by Walter S.

Meanwhile, migrants—especially Latin Americans—sustain much of the economy through invisible, underpaid work. Many came as students, but everyone knows that a student visa is, in reality, a legal strategy to be able to work. And they work hard: delivery, cleaning, kitchens, construction, dishwashing. “Unskilled” jobs, even though many of them hold university degrees, technical training, professional experience.

But here, the system is designed to block them. Validating degrees is expensive. Obtaining work visas is complex. Access to formal, well-paid jobs is locked down by bureaucracy… and by whiteness.

So, why do they hate us?

If migrants are the ones cleaning offices, cooking meals, delivering orders—why are they despised? Why are they blamed? Why are they expelled?

Perhaps because whiteness needs a constant enemy to survive. Because the system needs to point at others to avoid examining itself. Because as long as racialized bodies remain on the periphery—literally and symbolically—privilege can remain intact.

Writing, Naming, Resisting

Faced with this reality, what remains is the word. What remains is denunciation. What remains is writing. What remains is community.

I do not write this as a victim. I write it as a way of understanding, of rebelling, and of contributing to other ways of living and seeing the world. Because as long as the colonial echo continues shouting from the streets, the algorithms, and the institutions, we must keep speaking. And above all, we must keep making people uncomfortable.

Photo: painting from the “Dispossessions and possessions” gallery, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, photo by Walter S.

Comments

Post a Comment